Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

All significant change—let alone innovation, invention, or discovery—begins mostly as fiction. Calling it desire, intent, hope, or what-have-you doesn’t change the fact that it is presently not real. Change ends as non-fiction: a new reality that incorporates the change. The change leader’s purpose is to shepherd people through the journey from fiction to non-fiction—between realities.

In this respect, the change leader is in effect an entrepreneur. An entrepreneur is a creator, though not necessarily an inventor or an innovator. His or her sole purpose is also to midwife a fiction into a reality. Generally in a commercial context, the entrepreneur’s job is to make the new idea an accepted part of the firmament. Entrepreneurs are well-acquainted with sliding along the fiction curve—even if they don’t characterize it that way.

Accepting the view of an arc that embodies a shift from one reality to another (or, said less comfortably for some: from fiction to non-fiction), forces the practical question about the shape of that curve. Will fiction persist for a long time then rapidly (instantly) resolve to a new reality; or will the transition gradually become real from the outset, long before it is a matter of fact?

The shape of the fiction curve is important for change leaders and managers to understand. It should determine the approach to be taken to leading and managing the change, certain strategies and tactics being more suited to certain curve structures.

While the model obviously applies to innovation and start-up situations, rest assured it also applies to leading employees through a change within an organization. It matters not whether the change is to technology, tool, process, or structure. The common quality is an effort to adjust some aspect of people’s behaviours to accommodate the broader adjustments.

Projecting a fiction that it is credible, believable, and worth realizing is the challenge of every novelist, movie maker, and entrepreneur. Giving tangibility to what is essentially non-existent is no mean feat. In the software business it’s called selling vapour. Which is not for a moment to suggest anything untoward about it—unless designed to be a con or fraud. But that’s a separate matter.

While there is a world of difference between the objective of replacing old equipment with new and convincing people to sign in for a make-or-break innovation, they are essentially the same under this light. The first may be easier to dismiss—“It’s not fiction; it’s real,” perhaps, because the new machine is a tangible known.1 The second example represents an unknown, untested, intangible both at its outset and probably for some time after. It is sure to demand more of the fiction-to-reality process—the work of moving and leading the second change may be more arduous, but at core they are the same.

Still, for both and everything in between, critical challenges of fashioning reality from fiction must be attended to. Below is a list of the more prevalent, common challenges. They are not unique to change management. They may, however, be foreign (at least in description) to the change management circumstance and to specialists that have not operated in other domains.

In the domain of change to a corporate environment, successfully narrating and coaxing a new reality from a fictional goal tends to reflect the following characteristics.

Like it or not, life is about selling. You may not call it that. You may choose to avoid it. You may look down upon it. Yet one way or another, we all sell. That holds for change leaders.

A truth to take to the bank is that the greater the degree of fiction, the more (ongoing) selling is required.2 In the absence of anything tangible for a person being sold to wrap his/her heads around, words have to suffice. It is the art of persuasion as plied by con artists, salespeople, stock promoters, and innovators of any sort. Where there is fiction, the essence of (communication) activity is not informing but convincing—or persuading, if you prefer.

A valid concern in this race to enact a new reality is always that existing reality will impose itself upon the fiction being told. (Beyond infeasibility of the underlying intent/solution, we usually call this resistance.) This constant possibility reveals the real challenge of ensuring a fiction and its alleged value outweighs prevailing reality and comfort. The promise has to overpower the practical in a world biased toward the status quo. Distil the many tactics and responses to resistance in this context, and it’s apparent success tends to come in only one of two ways.

Fiction’s power is based on belief. It is why we have to “suspend disbelief” to enjoy science fiction. (Try as you might: you will never see a dodged 9mm bullet spiral past.3) Exactly as belief in such fantasy allows one to engage with that universe, so it is with the prosaic fiction of change within an organization. We need stakeholders to suspend disbelief for a while.

The good news (maybe) is that a typical organizational project’s visions and objectives—of change forthcoming—are far more credible and believable than what the Marvel Universe™ presents.4 In many cases the fiction is actually a matter of location as in: “It exists, just not here.” In other cases, the logical argument and case for change traces the contours of value and achievability. It is believable reality foretold. The critical challenge is to make the vision and the change and the conditions sufficiently real to be believable and, moreover, believed.

It ought to be self-evident, but may need saying anyway: belief is not dependent on facts and data. Remember this because at some point the question of what to communicate will arise. Again, lest it not be obvious, “just the facts,” is not the best starting point. The amount and nature of fact available and/or provided has to be sufficient for plausibility but not so much as to genuinely entertain critical scrutiny/challenge. By that, I mean there is a fluid line after which more fact turns willing belief into challengeable certainty.

This old saw is mother’s milk for strivers everywhere. Sometimes it has a more socially acceptable form such as, “Dress for the job you want, not the one you have.” Always, its categorical and explicit counsel is to create and perpetuate a fiction until it is a reality. Funny that.

The change leader will and must be prepared to do precisely this. That is not to suggest pantomiming processes that do not yet exist or operating within an organization structure that is yet to be. That would be ridiculous. In this circumstance generally (because every change/transformation is unique), fake it until you make it refers more to the apparent tangibility and inevitability bestowed upon the vision and/or change, in word and deed, by the change leader/sponsors and organization generally.

This can range from extremely simple things like verb tense to more delicate attitude/behaviour adjustments. The simplest is verb tense. Projects and transformations, especially at the earliest stages, tend toward future or conditional (or worse, future conditional) verb tenses. This is honest and factual. After all the vision is in the future and at the very least conditional upon some (extended) activity being performed. Wrong! The present tense is faking it until you make it. It’s more certain—or certainly less tentative. And people generally like, need, and crave certainty.

Within the organization more broadly, there are undoubtedly behavioural or attitudinal parallels to what the change anticipates. If, say, prevailing behaviour reflects the existing state (e.g., risk averse), informally “fake” the change. Categorically appear more risk-taking. If a behaviour in some part of the organization tracks to the desired “to be” state, make it the model, bellwether, or north star. Call it out. Laud it at every opportunity. Promise that reality as your envisioned reality (but still a fiction).

Although the change leader’s objective is to change behaviour—arguably the sole purpose of change leadership—one critical lever of success (or failure) is attitude. The psycho-social dynamics of the relationship/impacts between behaviour and attitude is not wholly clear, linear, or—actually—fully understood. What is clear, however, is that at certain levels they are mutually causal and reinforcing.

To wickedly oversimplify, while we know that specific attitudes (e.g., favourability toward novelty and trying new things) are behind and affect specific, identifiable behaviour (e.g., willingness to change and experiment), what is equally true is that specific behaviours affect corresponding specific attitudes. Force yourself to play with snakes and your attitude toward serpents will eventually shift.5 Moreover, maybe over time those specific attitude shifts colour change to broader general attitudes. To fulfill the cycle, theory (and practice) suggests the attitude’s new alignment and strength (both specifically and generally) would positively affect habituation of the behaviour.

The point is that both behaviour and attitude are relevant, and their mutual causality is usable in the context of a fiction that dissolves into an expected, desired reality. While the goal is specific behaviour change “A,” it may be profitable to insist on a complementary behaviour “B” to change attitude so that it, in turn, will help get you what you want down the road on behaviour “A.”

Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, and even Lee Iacocca—and the people that supported their changes, innovations, and transformations—were eventually obliged to prove the substance of the stories they were telling. In commercial jargon and change management training these proofs are usually referred to as “wins.”

The idea is that people will shift or change more readily if they see that there are proofs the fiction is being realized. (Hence why these proofs are referred to as wins.) The point is that propagating a fiction in a change/transformation circumstance demands there will be some proof the fiction is not actually a fantasy. Or worse, a delusion.

The good thing is that proving does not require 100%, all-or-nothing manifestation. In practice, proof comes in drips and drabs. The mere hint that proof is on the way is sometimes sufficient to allay fears and resistance, and incent further behaviour change. Said another way, change success is not typically a big win, but little wins repeatedly achieved. Once again bolstering the “quick wins” strategy.

Given that a fiction is unlikely to change to a reality in an instant: developing, expanding, and growing proof is essential to sustain remaining fiction through to it becoming a reality. In other words, you’ll have to fake less and less as time wears on.

That’s the question, isn’t it? The simple answer is “As long as it has to.” Although that’s neither satisfying nor bankable. What is repeatedly evident and proven is that a delusion—even (or maybe especially) among a large group—can be created and maintained for a long time under the right circumstances and with dedicated attention.

The conditions for most organization change are generally not so conducive—barring a messianic leader, of course. (And even then…) This means that the fiction of a change or transformation has a half-life that depends on story, proof, communication intensity, and even charisma (of the storytellers, of course) that may be different depending on the stakeholder in question.6

So, unsatisfying as it may be, in a change/transformation situation the fiction must last as long as it has to. The practical reality and velocity of achieving the underlying goal is obviously key as an outer bound, but not an essential factor. However long the fiction must last, though, ought to affect the shape of the “fiction curve.” The subject to which we now turn.

From the outset, the end-state of any change in an organization that warrants “change management” is to some degree a fiction. That is, to greater or lesser extents, the vision represents a novelty: a good and pleasing picture, with sustaining logic and an implicit worth to pursue it.

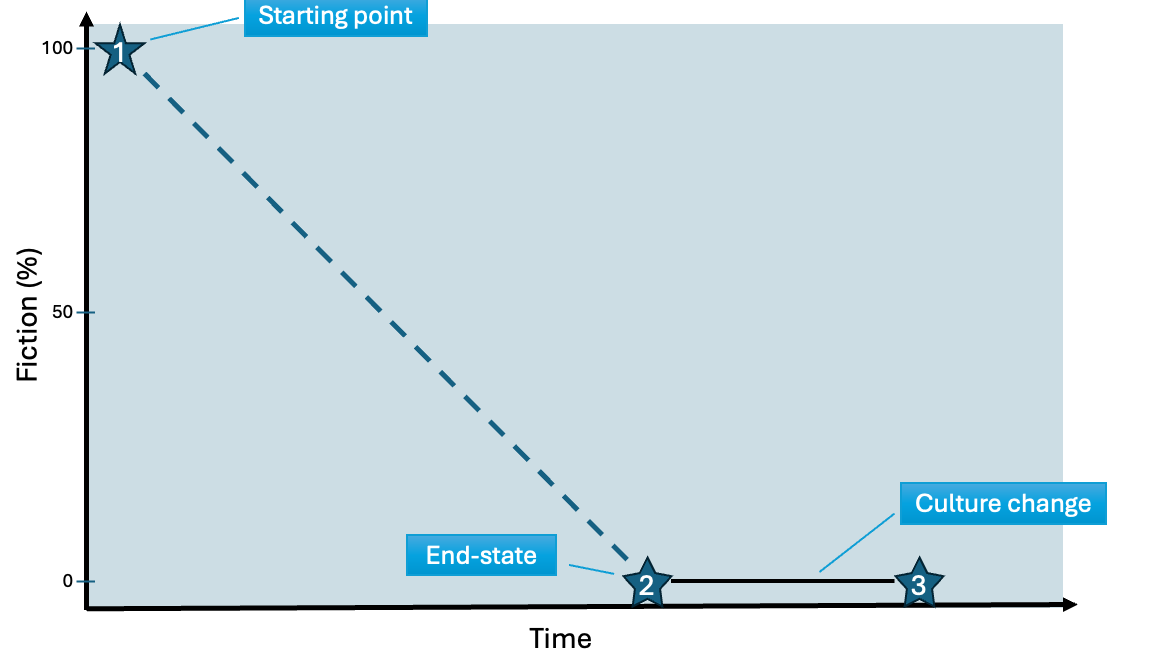

Figure 1 illustrates this idea in two dimensions: Fiction (Fiction<—>Non-fiction) vertically and Time on the horizon. The objective of any project and the change it brings is to move from position 1 (the Vision stated today), where the goal or vision of the change is a complete fiction, to position 2, where the project is fulfilled and the Vision is real. In my language here, it is now non-fiction. Beyond that point, to the right, continued action must be taken for some period post-achievement of the goal or closure of the change effort to reinforce behavioural commitment until cultural change takes hold and the desired behaviour is habitual at position 3.

Figure 1 – The decline of fiction/rise of reality over time during a change

The chart is relative. The starting point—the Vision (today)—is always 100% fiction regardless of whether the vision is proximate, innovative, or a fever dream. The only thing this qualitative distinction does is alter the slope of the curve per Figure 2. This, again, is conceptual. But for this purpose it hardly matters.7

Figure 2 – Fiction dissipates; the only question is over what time

The important point being revealed is that over some period of time, for any project or transformational change, there is an absolute, immutable certainty that the change circumstance will move from a state of 100% fiction to 100% reality.

The point of project and change management, and especially leadership, is to ensure the defined target destination (“Vision”) is reached. Just because it’s designated, stated, and even described does not, however, mean it will survive prevailing circumstances—most specifically any resistance—and be realized. Remember, position 2 is the result of a goal described as a vision at position 1 (i.e., at that earlier time). It is not by any stretch of the imagination certain at that time (position 1), merely promised to be so at some specified (or indeterminate) point in the future. Beyond realizing the underlying “solution,” this means shepherding the perception of reality until the reality sustains and validates the perception.

`Cheshire Puss,’ [asked Alice.] `Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

`That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.

`I don’t much care where—‘ said Alice.

`Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,’ said the Cat.

`—so long as I get somewhere,’ Alice added as an explanation.

`Oh, you’re sure to do that,’ said the Cat, `if you only walk long enough.’

As the Cheshire Cat points out to Alice, you will get somewhere. But since organizational changes are not adventure vacations and tend not to be in Wonderland, somewhere is not good enough. The whole point of describing a target, vision—a goal, is because it is the desirable end. Which is then to state the obvious: the goal of (project/change) leadership is to ferry a journey to a stated destination. Therefore, the optimal difference between the position 1 Vision when stated as fiction at time zero and position 2 at time “achieved,” is NONE. Variance here is the measure of failure in the project/change.8

While our goal, as change project leader, is to manifest the originally described vision as reality, we have to recognize it does not happen all the time. (As the statistic bears out.) But, short of staying at the same place—that is, making no change, which would be utter failure—the change achieves something and gets somewhere. That point, where we end up—call it position 2 or 2’ or 2x, is the new zero-fiction reality.

In a practical sense, practically applied, the path from position 1 to 2—and even on to position 3—would be meandering. At the very least it would not be a straight line. If project/change experience generally is not enough to make this a statement of accepted truth, life lessons to bear it out can be found everywhere. Moreover, because “everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth,” we can count on there being evolutions to the plan and even the goal that result from conditions encountered in the ring when the fight starts.9

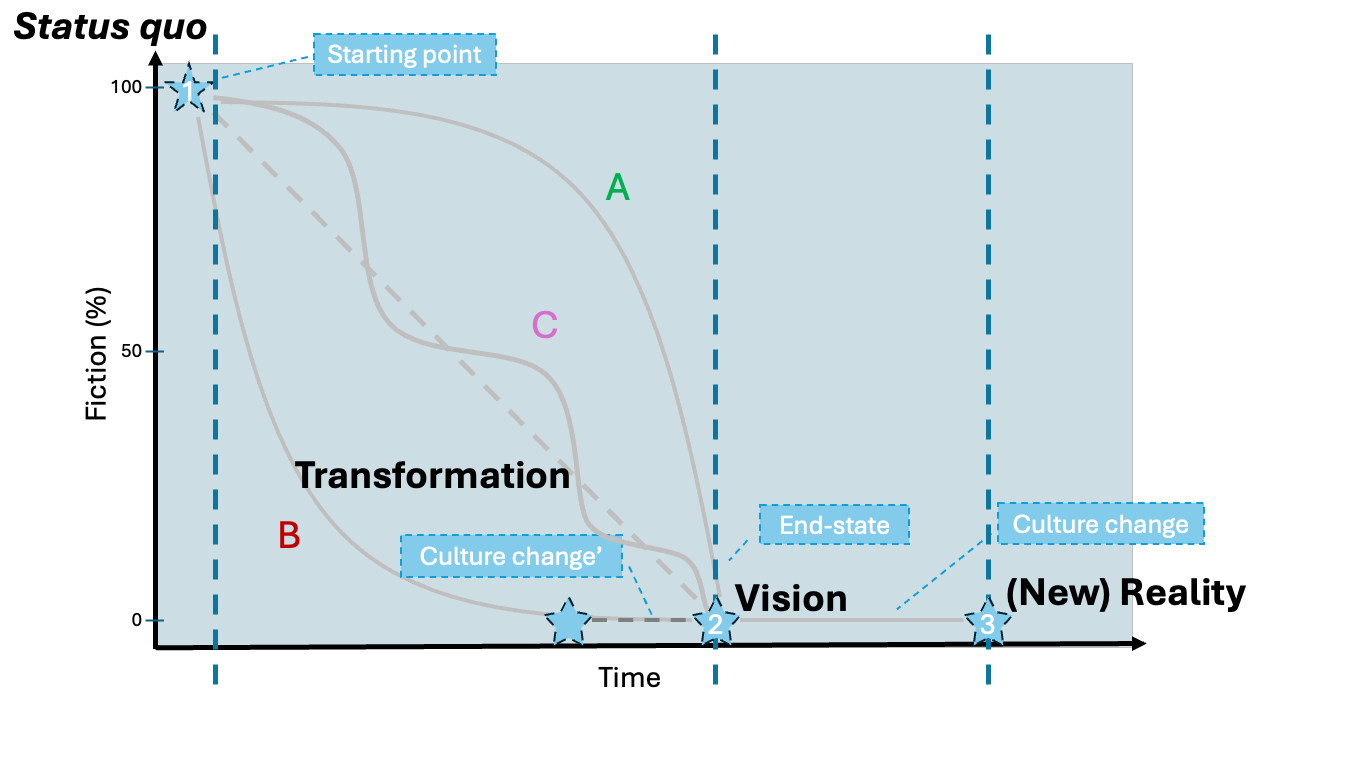

As illustrated in Figure 3, below—an elaboration on the basic chart, there are paths on either side of the straight line. For illustration one is provided on either side and labelled as curve A and curve B. These can be read as slow start and rapidly accelerating change (A) and fast then diminishing change impact (B). A serpentine curve, shown as C, is possible (if not probable). We will consider them more fully below.

Figure 3 – All curves

For the sake of illustration and instruction, non-linear curves expose then clarify reason and purpose behind given strategies and actions in the journey from fiction (1) to reality (2). Note that while a curve can be chosen at a strategic level, ultimately conditions on the ground will have critical determining effect on what side of the line from (1) to (2) is pursued.

Curve A represents a long time for the fiction of the stated goal to begin revealing itself as reality. When it does though, perceived change may come fast. In this way, curve A resembles “revolution.” Whatever is going on is unobserved—maybe unobservable—maybe nothing more than activity (even irritating activity to some) until it is manifest in a dramatic change of state. There is, however, a lot going on. Significant change is being set up. It just doesn’t feel that way to the majority. For the leader, the tension and challenge is persisting in the people—and other—change with limited proof of eventual success.

This curve requires faith to support the longer period of promise. Leaders must maintain faith that their vision and intent is right and achievable. (“Stay the course.”10). Faith from followers, who are substantially without proof, has to be stoked and affirmed by the leader. Obviously, this path is much is more work for the leader. It can demand work in every respect from charismatic persuasion to retelling the tale—imbuing it with the smallest bits of practical evidence, executing the invisible work of change in the background, and ultimately, moving those who are to change to persist with apparently ineffective project work.

More obvious resistance is more likely on this path. The resistance will have every cause to arise, increase, and expand over time for two reasons. First, the absence of proof will strengthen counter-belief (in the status quo) as time proceeds. The absence of evidence in favour is, typically and sadly, perceived as evidence against. This is human nature. Duration is the second reason. More time with unrequited action is more time for grumbling and doubt to fester… and root.

There is likely a tipping point at which evident, successful change will happen fast. This may present similar but different challenges for the leader. During the preceding period (when faith was required to sustain and drive and behaviour change preparation), it’s reasonable to assume those preparations happened. Maybe it was reluctantly or skeptically for some, but it was done and internalized. Should all those sub-perception-level behaviour/attitude adjustments have not been made and internalized on faith, when the rapid change comes, those who must now adjust will be far behind. It will be—effectively—a surprise and a rush to adjust will ensue. Surprises tend to create panic responses, of which resistance is foremost. These have to be handled differently, meaning the leader has to (non-trivially sometimes) shift leadership approach.

The change leader may want to know what makes for such a tipping point and how to precipitate it faster. That is a matter of structure, which leads us to Path B.

Curve B represents the most-desired and oft-recommended approach, one that uses quick wins to reduce (early) friction. One argument in support of this goal is that the longer or more regularly friction can be deferred, the less likely it is to take hold. First, counterbalancing reality—the quick wins—inhibits it. Second, eventually the full change is in place and a new status quo reality reigns. This, of course, assumes friction (resistance) will arise—is, in fact, omnipresent—and that the role of leaders in averting it from ruining the plan is to hold it at bay until circumstance (the positive change impacts) obviates or overwhelms any resistance.

In this scenario, along Path B, reality is continually altered with little changes along the way. The size and nature of these proofs is circumstantial, but they are optimally planned, ordained, and readily digestible. The fiction disappears gradually and persistently, perhaps even early as depicted in the bold relief of the illustration, with the final bits of the new reality squeezed out at the end.

Of course, this means the material elements and changes of the underlying project can be and are rendered real earlier. Most significantly, this evolution is perceived as actual and successful along the way, mitigating a leader’s reliance on followers’ deeper belief and faith as would be required for a deeper/longer fiction per curve A. Moreover, there is also more time for each successive smaller change to settle in and be accepted. Certainly relative to Path A.

In short, quick wins move the vision toward reality faster (i.e., reduce the proportion and duration of fiction). That makes it at least feel like faster overall change—despite both curves reaching the vision at the same time. The benefits to this approach are well-documented by almost every methodology and there is no arguing with the validity of the small wins strategy. The situation works with and for the change leader because the momentum of early and ongoing proof can be used instead of faith despite any remaining belief required from those being changed. If the project is long, small wins performed with finesse can make it seem as though there is effectively “no” change; it is an invisible and even inevitable evolution. (Think about proverbial boiling frogs.)

Squiggly curve C approximates reality—not necessarily intention. Nobody would plan this path—though there is merit in the approach and a certain inevitability, so maybe everyone should plan for it. It represents the faster-slower changes to the state, condition, or fulfillment of the project: the vertical segments representing points where implementations are made, and the horizontal periods revealing where it took longer in the background before some specific promise became real.

As a representation of reality, Path C is still somewhat idealized. That is, the curve always moves from left to right at a negative slope (or neutral at worst). Real projects, especially “innovations” or those in particularly ambiguous circumstances, may actually go upward, indicating reversals or other adjustments. For our purpose though, the serpentine curve affords a reality check. (Pun intended.) The journey from fiction to non-fiction (for both project and behaviour change) will be marked by periods of obvious progress as well as interminable periods of action with seemingly nothing to show for it.

For the change leader, it ought to make clear that none of the techniques for dealing with either rapid or delayed change can be stowed away. This is true regardless of strategy and intent. On the journey from fiction to fact, the many aspects and facets of the story will change independently, usually at their own pace. They must be coordinated and maximally employed by the leader. In short, nothing is as clear cut and clean as curves A and B.

For a project or transformation, the end-state vision is an objective that is—at the outset—a fiction. The goal is to make that fiction a reality. The journey from now to then—plan and action—is the story and lived reality of the change. The good news is that whether it be very modest alteration to a process or a wholesale business transformation, there is a broadly predictable journey with consistent elements.

The elements and steps relate to the change curves. Understanding the elements’ purpose and sequence benefits not only the planning of the journey and story (i.e., tactics used), it helps set stakeholder expectations. Moreover, the elements always factor into the “plot” and “episodes” (to use storytelling terminology), which ought to help ensure thorough preparation.

So let’s look at the elements as exposed in Figure 4.

Figure 4 — Elements of the journey

On the left side, at the outset there is a circumstance: the tools, technologies, behaviour, culture, etc.—forces that propel and enforce prescribed behaviour. There is also a desire to improve something about it. (Note: The desire is never universal, but the decision to alter the organization in a way that will affect many others who are not part of the decision—is universal.) What matters is that the desired change—which may be relatively pedestrian, quite large and material, or fully wholesale—has a goal state and that state does not presently exist. That goal will not exist until the change has been successfully implemented. Until then, it is a fiction—a fictional Vision, if you will.

More categorically for our purpose (i.e., the people side of change) the status quo situation applies to both the underlying business process or technology or what have you AND to the behaviour by relevant employees. There is a way things are done now; and to greater or lesser degree that has to change. To the extent it is yet even known, that new approach is also a “fiction” inasmuch as it is not the way things are done and nobody (here) does it that way.

At the other end of the curve, on the right side, is a representation of the vision (position 1) as is supposed to be in the future after the selection, implementation, and process/procedure-based behaviour change (position 2). It is an idea—at least at time zero when it is truly a fictional vision.

The desired changes are wrapped in an end-state vision as complete and palpable as can be made, typically involving a business case and list of benefits. Generally it starts from the effect: on profit, on market share, on what-have-you. However it manifests, this all constitutes rationale: why this needs to be done and this state achieved. Assumptions are made; projections are conjured. Planners and architects and so forth create a path to this desired state. Various tangible proofs, such as others (competitors or models) that are doing this or who have made similar changes, are rallied to the cause.

Remember: at the outset, all these are fiction to be given shape and form—optimally as vivid as a hologram. The journey must also be envisioned. This is the sell. It must all feel like reality for the so-called sober-minded people to buy in. (For this, make it seem like a choice based on competing realities or guarantees—at least to some reasonable extent.)

The same applies to all those who would have to change. They must see their new behaviour and their new world in technicolor and so be incented to move from their comfortable old one. However it is approached, by whatever means are necessary, ultimately these people are being convinced to do something unproven, as opposed to persisting with something proven—and comfortable, with their livelihood and self-conception in the balance. The change leader sells that fiction.

Eventually, through a process of development that may include quick wins and step transitions (i.e., smaller steps and proofs similar to getting a non-swimmer into the pool step by step, ever deeper), the fiction gains form and shape. It becomes ever more tangible. The change unfolds like a building arises from blueprints and scale models. Through this period the fiction solidifies into non-fiction. The theories and assumptions—the imagination—becomes real.

Eventually, as the endeavour gets close to completion, the proportion of fiction to non-fiction reverses. The situation is mostly real. As we know, though, the challenge is that in a project/transformational change situation, the final reality of complete change is always subject to the behaviour and change of the people. The building may be built and completely non-fiction. But the vision is unrealized and hence the change is incomplete. In the realm of internal change, this is like the technology being replaced, the organization structure being implemented, the strategy being adjusted… and yet the organization stubbornly continuing to behave as it did before, not as it should now.

A good example of project changes being complete but the change vision unfulfilled is the London financial district known as Canary Wharf. This area was conceived and initially developed in the 1980s by Olympia & York, the now-defunct Canadian developer owned by the Reichmann brothers. Though the buildings were built, it was not until a long time after O&Y had vanished into the mists of commercial history that Canary Wharf fulfilled the original dream of becoming the epicentre of London’s financial district.

This dominant element is, indeed, what substantially constitutes change leadership and management for most people. It is the period during which the active transformation is underway be that the development and implementation of technology, solution deployment, process renewal, organizational restructure, and so on. It is when change managers ply their trade of coordinating communications, training, engaging with sponsors and stakeholders, etc.

There is no value in elaborating on what goes on, how it is done, or what to expect in this period because it is the context of all change management technique and theory. For our purpose in this framework, it is merely the time when non-fiction is fabricated from the outlines and plans of the fiction described as the goal or vision at position 1.

Whether the path/curve being following is A, B, or C is not material here except, as previously noted, for how the underlying action is being executed and what change management techniques are most relevant and appropriate to that plan through the course from fiction to reality.

At this point, the goal is realized or at the very least the project has ended. Both may be true, which is the intended outcome. It is, however, definitely possible the project ended and the goal only partially—mostly—realized as envisioned or re-envisioned. (Or maybe fully realized plus.) In any case, a small change or significant transformation has happened.

Even if the initiative is considered or is even empirically an exact success, there will almost certainly be a discrepancy between the vision from the outset and the realized change at the end. It may be trivial or material. That makes no difference and is to be expected because the journey should really be one of discovery and customization—at least to some extent. The precise nature of the end is and cannot be fully known at the outset in any case. Undoubtedly things will be tweaked—the sharp edges of intent smoothed out by the rough abrasive of interpersonal negotiation with and among stakeholders. And that’s probably how it should be.

In addition, there is always recidivism (even from adjusted intentions). People are people; we slip. But since impacted people need to change completely to correspond with the underlying changes, reinforcement and correction are required. For what it’s worth, for my money, reinforcement is the most valuable exposition of change management discipline. It alone recognizes that, except where structure inhibits it, backsliding into old habits is not merely common but likely. Encouraging projects and organizations to remain active and vigilant during post-completion consolidation is a big win.

It may be counter-intuitive and frowned upon by serious, just-show-me-the-numbers management/executive types, but the truth and practicality of this way of thinking about leading change cannot be denied. The future (vision) is fiction today. Getting to, let alone existing in the reality of that vision will require impacted stakeholders change (some) behaviour. The creation and deployment of both those fictions as a new reality is the change leader’s sole purpose.

Apart from and beyond orchestrating the practical actions that will realize these realities, this way of thinking frees the mind to consider, appreciated, employ, and struggle with the omniscience of the fiction creator to chart a credible path from fiction to non-fiction.

Institute X is a transformation leadership consultancy and transformation/change leadership coaching firm. One of its online presences is The Change Playbook. Be sure to check out the abundance of practical and pragmatic guidance for all aspects of making change happen. Subscribe to be notified of new, fresh content.